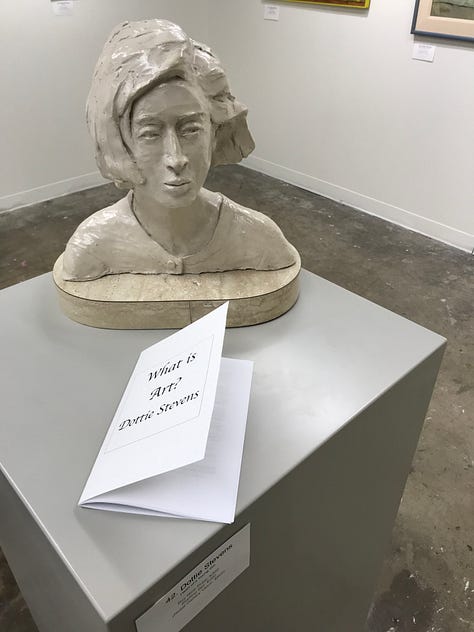

What is Art: a Century of Impressions

How fine artist Dorothy Silverstein Stevens left her most essential question to me to answer

Of all the remembrances I explore in Releasing Memory, those with my mother are the ones I find to be most emotionally fraught.

Dorothy Silverstein Stevens was a gifted painter, sculptor, and ceramicist for whom making art was a lifelong passion. Her pursuit of creativity and beauty led her to fill hundreds of canvases and sketchpads with her work.

Her questions about the point of it all led her to debate the question, “What is Art?” in journals, poems, a play, and the mini-memoirs she wrote in her dotage, long past the time she would have stamina enough to stand at easel with brush and palette for hours—or days—on end. Or pound air bubbles out of the mound of clay she used in crafting her “Kooky Kids” sculpture series.

As Mother’s Day approaches, and along with it, the unearthing of memories of mothering and being mothered, and now, of grandmothering, I am reposting a blog I wrote for the Art Academy of Cincinnati (AAC) in advance of a 2019 retrospective show held for their oldest known alumna, Dorothy Silverstein Stevens, on the occasion of the first yahrzeit (anniversary) of her death in 2018.

I’ve added thoughts about Mom’s legacy beneath that original post—and my best answer to the question, “What is Art?” that haunted her to the end.

Women of Dottie Silverstein Stevens’ generation came of age in a time when most occupations were not open to them. And self-promotion frowned upon.

Their work was in the home: raise the family, keep a nice, clean and orderly household, serve as gracious hostesses or guests and be good helpmeets, volunteer in the community, and get together for bridge or mahjong with “the girls.”

They could have hobbies: cooking, painting, playing piano.

But to work outside the home, much less to promote one’s artistry in the marketplace, would be frowned upon.

“Father Knows Best” was not just a TV show, but a way of life.

My mother, born in 1918, was typical of her era in that she did all of the above, and without reproach.

But her passion was for her art.

She painted, sculpted, took classes, taught them. . .and never let go of the question that drove her all her life: “What is art?”

All the while, seeking to capture her own version of it.

Even though she thought “selling” herself and her work was unladylike, she found a way. Dottie entered juried art shows, and won. When her paintings sold, she kept detailed records about the purchaser, price, and date of sale, along with a Polaroid or Kodak picture.

She kept records of it all on file cards, painstakingly handwritten, with xerox copies in loose-leaf binders—this being the days before computers could spit out copies on demand.

But her journey started by accident, at the tender age of 6, in 1924.

“From the very beginning, it was all based on an innocent, naïve misconception.”

~Dottie Silverstein Stevens, on how she became an artist

A teacher, a poem and a shadow as gifts for a lifetime

Here’s how Mom told the story in a mini-memoir she wrote late in life:

“In elementary school, we had a wonderful teacher who inspired all the children in a very clever way. She promised a special reward if we behaved and worked hard.

“She would read a poem to us and then let us draw a picture about it. One day, our reward was a charming little poem by Robert Louis Stevenson, “My Shadow.”

I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me,

And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.

He is very, very like me from the heels up to the head;

And I see him jump before me, when I jump into my bed.

“After reading it aloud, we all took out our crayons to draw a picture about the poem. As Teacher walked around the class, I was surprised when she paused at my desk and asked me to come to the front of the room and hold up my picture.

“Then, she proceeded to take me to all five other first-grade classes to display my ‘work of art,’ to hold up my drawing in front of all the other children as an example.”

Mom never thought to question why.

When little Dottie told her mother about this honor, my grandmother immediately proceeded to buy the six-year-old a beginner’s set of oil paints, a small palette, and a canvas board. She was signed up for art lessons after school and, in time, made her first oil painting—a copy of a beautiful lady by Thomas Gainsborough.

From hobby to profession

Cincinnati was sponsoring a city-wide art competition downtown, called “Girls Hobby Fair.” After investing one dollar in a picture frame, my grandmother submitted my mom’s earliest still life: Two Books and Brass Candlestick. It won a first prize blue ribbon, and a $25 gift certificate to Wilde’s Art Supply Store. With that coveted certificate, Mom bought her first wooden easel.

Art became a major part of her life. She pursued formal training in great art schools, beginning with the Art Academy of Cincinnati in the 1930s, the Cincinnati Art Museum and later in universities and museums. During World War II, she studied at the Chicago Art Institute and did graphic art design working for the Manhattan Project in Chicago, where my father was then stationed in the Army.

She was inspired by the Impressionists, and first copied, and later innovated on their style. She began experimenting with sculpture and printmaking, and ceramics.

Extensive travel with my dad, David Stevens, further enriched Mom’s experiences. Many of her paintings took their inspiration from their travels around the world, making it altogether fitting that the proceeds of the art auction would go towards funding a scholarship for AAC students to study abroad.

In her 90s, when the physical processes of painting and sculpting became too demanding, Mom turned to writing. She wrote a play, “What is Art?” to explore this question using words as her medium.

And after she gave up painting and sculpting, she used to say she was always painting in her mind. For her, art became sustenance.

But she never got over thinking that the drawing that launched a career and a passion for art was really a happy mistake.

Again, Dottie’s words:

“Thinking about that early inspiration, I can’t believe there was really anything aesthetically remarkable about my picture.

“My guess is, that while other kids were naturally drawing a little child with its detached shadow somewhere nearby, perhaps my portrayal showed a little girl with her shadow attached to her feet, and with its shadow laying horizontally on the ground, as shadows do, according to the laws of physics and the direction from which the light was slanted.

“In any case, because of my early misinterpretation of my first-grade teacher and her encouragement, a subsequent whole world of art opened up to me.”

Inspiration comes full circle

It is fitting, then, and a great thrill for her family that, having started with the early inspiration of a teacher, Mom’s art and the Wilder scholarship it endows would pay it forward: to support, to inspire, indeed, to fuel, an art-filled future for students at the Art Academy for generations yet to come.

Valuing a life of creative expression

Mom was given the option of holding that retrospective at the Art Academy to celebrate her 100th birthday, while she was still alive. Living in Sarasota, Florida, she would not have been able to fly to Cincinnati to see it in person, but could certainly have participated by video.

My mother’s legacy to me, as a writer, playwright and poet/science writer and social marketer, is complicated. She grappled with that question “What is Art?” all her life.

For her the question was philosophical: how are Jackson Pollock’s paint dribblings on canvas considered artistry? How can a toilet by Marcel Duchamp, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz, be considered a masterpiece?

In fact, when I visited the Art Academy in 2019 before the opening of Mom’s retrospective and took in the diverse and inspiring offerings by students currently studying there, I wondered what Mom would have thought. These young artists were definitely not part of any Impressionist school. Many of the more avant creations on display were works Mom might have tsk-tsk’d as kooky.

Hoodwinking the public. Pulling the wool over the eyes of gullible collectors, sheep, she might muse.

When it came to Mom’s own art, she was certain of its intrinsic value. She was dedicated to capturing, interpreting and reinterpreting the beauty she saw in her subjects.

But she was afraid to put herself out there on the public stage. To market her own work. Or, as she would put it, to “sell herself.”

And though my own “art” is different—prose, poetry and playwriting—I have chosen to put myself out there. Not to “sell” myself, but to offer insights into the human condition using comedy, tragedy, imagination and creative inspiration to entertain, amuse, enlighten and engage readers, young and old.

“But you’ll never make a living.”

(An anxious mother’s warning to her daughter, a writer.)

When I attended the opening for my mother’s retrospective at the AAC, fittingly titled, “What Is Art?” I felt like an imposter. After all, I am not my mother. They were celebrating her work, not mine.

The number of friends and acquaintances who attended—who remembered my mother—was amazing. By that time, she had not lived in Cincinnati for almost 40 years. She hadn’t studied art at the Academy since almost 20 years earlier. There were friends and associates from many walks of her life—almost all of them touching on the arts—who came that day to honor her. And current students at the Academy as well.

After welcoming remarks by the then-newly installed AAC president, Joe Girondola, the Academy’s archivist took us on a stunning narrative tour of Dottie’s works, showing how each of her teachers and influences—some of Cincinnati’s finest artists and art teachers, from Paul Chidlaw to Julian Stanczak to others whose names I didn’t recognize but who, besides teaching, themselves had made outstanding contributions to the arts—had made an impression, had left their mark on hers.

Suddenly, I could see Mom’s body of work in a new light, not as a standalone tribute to my mother, the painter. But to a lineage of artists who themselves interrogated this question, “what is art?” and came up with their own expressions of it, building on the past and leaving their own unique marks to the future.

In that moment, I found an answer to Mom’s obsession, the question that preoccupied my mother throughout her life.

What is art?

Art connects us.

That’s the legacy my mother has passed down to me. To create for the joy of it. For the connection. For the beauty of expression. To leave a mark.

To pass along inspiration to successive generations.

“We may not make a living from art, but we will make an impression.”

~ Robin Stevens Payes, daughter of the artist

It is one thing to engage in creating to feed yourself, quite another to feed your soul. To touch the hearts of others. And to feed the hearts and souls of so many after you.

All three are necessary contributions. They contain seeds to sustain what is human in us. To inspire humanity. To meet us where we are and carry us where we may want to go next.

Art is inspiration, love, connection. Art is life. And that is just the truth of it.

Such a lovely tribute to your talented mother! I love hearing stories about those first moments of encouragement and what can blossom from them. In your mother’s case, a field of valuable, beautiful sustenance.

I really enjoyed this tribute to your mother - thanks for writing it <3

I'm so curious about this interplay between mundane daily life and making art (for a living or not); it's even more fascinating to consider your mother's point of view, as someone for whom 'making money' was consider immoral (I'm assuming - since you say 'unladylike').

so many thoughts come to mind!